Strong Trade Winds and Trade Wind Swell (SW, HS)

Seasonal: Winter (December to March)

The northeasterly Trade Winds are dominant feature of the weather and climate throughout most of Micronesia during the winter. As a rule, Trade Winds typically reach peak speeds of 15 meters per second (35 miles per hour) in regional waters during episodes of enhanced Trade Winds. While not damaging, these frequently require small craft advisories and airport weather warnings. Trade Winds rarely reach gale force in regional waters. Because of their long fetch distances from near Hawaii into Micronesia, episodes of enhanced Trade Winds generate high surf, which has been known to cause minor coastal inundation. A notable historical inundation on Majuro in December 1979 was caused by strong (near-gale) Trade Winds between that location and Hawaii. The same event caused high surf of 12 to 14 feet even on Guam. Hazardous surf generated by enhanced Trade Winds is typically 3 to 4 meters, and rarely exceeds 5 meters.

Trade winds are a feature of the dry season, and are not typically associated with the occurrence of damaging or severe weather. Enhanced trade winds in regional waters often occur after the passage of a shear line. Shear lines are the southernmost extension of the cold frontal systems associated with mid-latitude cyclones. Shear lines are named for the increase of wind speed that occurs with their passage, with little or no change to the prevailing wind direction. A band of low clouds is the readily defined signature of a shear line on satellite imagery. These relatively narrow bands of low clouds bring showers for a day or two as they pass through. Rainfall during a shear line passage is often on the order of one-half to one inch, but can be greater if convection forms along the shear line.

During the summer trade winds are less frequent and less intense, and are often replaced by southwest winds when the monsoon trough extends into Micronesia or by tropical cyclones.

Other event types of the western North Pacific include

- The Southwest Monsoon and Monsoon Squalls

- Tropical Cyclones (Typhoons) , tropical storms, and tropical depressions

- Other types of Thunderstorms

- Extra-tropical Storm Surf

- Extreme Tides

The Southwest Monsoon and Monsoon Squalls (SW, HR, HS)

Seasonal: Summer (JASO, or June to October)

The monsoon trough is an important feature of the atmospheric circulation pattern of the western North Pacific. By definition, it is an east-west oriented trough of low pressure, and its axis demarcates a wind shift from easterly winds to its north to westerly or (more commonly), southwesterly winds to its south. The monsoon trough is inherently migratory. It tends to form at low latitude (south of 10° N), and then drifts slowly to the north and west. As one monsoon trough exits the local region, another often reforms at low latitudes and the cycle repeats.

During the summer, a monsoon trough frequently extends into Micronesia. The southwesterly winds to the south of the monsoon trough axis can reach gale strength, with embedded squall lines containing the highest winds. Sometimes know as monsoon surges, episodes of strong southwest wind may last for more than one week. Monsoon squalls bring sudden white-out rainfall conditions, storm-force wind gusts, and sometimes frequent in-cloud lightning. The long fetch of the southwesterly winds generates hazardous surf on the western shores of islands and atolls of Micronesia.

Large cyclonic disturbances developing in the monsoon trough are known as monsoon depressions. Monsoon depressions are the seed disturbances for nearly two-thirds of the western North Pacific basin tropical cyclones.

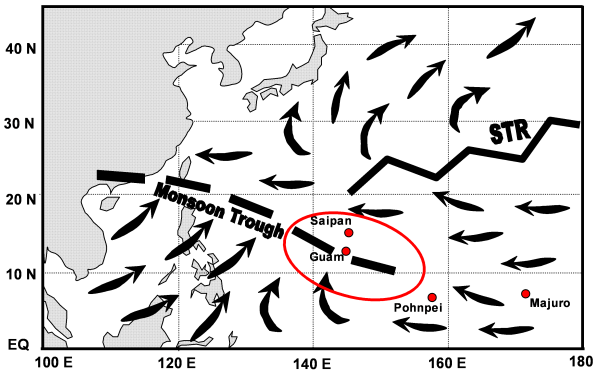

The average low-level wind flow of the western North Pacific during summer.

The monsoon trough extends to near Guam, and the subtropical ridge axis (STR) stretches across

nearly the entire North Pacific at a higher latitude.

ENSO has a substantial effect on the behavior of the monsoon trough in Micronesia. During strong La Niña, it is weakened and pushed far to the west. During La Niña years, easterly low-level wind anomalies dominate Micronesia, and southwest winds may not reach Guam or regions eastward from there at anytime during the summer. During El Niño, the monsoon trough extends further eastward than normal and is established earlier in the year than normal. This leads to an enhancement of early season typhoon formation, and an eastward displacement of typhoon formation. During El Niño, the risk of a typhoon strike on Guam is elevated to 1-in-3 from the normal 1-in-7. At locations in eastern Micronesia (e.g., Majuro), typhoons are almost exclusively experienced during El Niño.

Other event types of the western North Pacific include

- Strong Trade Winds and Trade Wind Swell

- Tropical Cyclones (Typhoons) , tropical storms, and tropical depressions

- Other types of Thunderstorms

- Extra-tropical Storm Surf

- Extreme Tides

Tropical Cyclones (Typhoons), tropical storms, and tropical depressions (SW, HR, HS)

All Year, with enhanced activity during late summer through December

Low pressure, cyclonic systems originating in the near-equatorial oceans are known as tropical cyclones. When typhoon intensity cyclones make landfall, the combination of fierce winds, intense rains, and high surf can be devastating (e.g., Paka on Guam in 1992, Sudal on Yap in 2004). Most typhoons that strike islands of Micronesia are home-grown. Beginning as monsoon depressions somewhere in Micronesia, they step through the intensity thresholds and strike islands as depressions, tropical storms, typhoons, or super typhoons. Occasionally a tropical cyclone which formed in the eastern North Pacific or Hawaiian waters moves west into Micronesia (e.g., Paka in 1992).

Typically typhoons move through Micronesia on a track from east to west. They also tend to gain latitude as they move westward. Tropical cyclones that form in Micronesia often end up in the Philippines, Taiwan, Japan, or miss land altogether and re-curve into open water on their way to higher latitude.

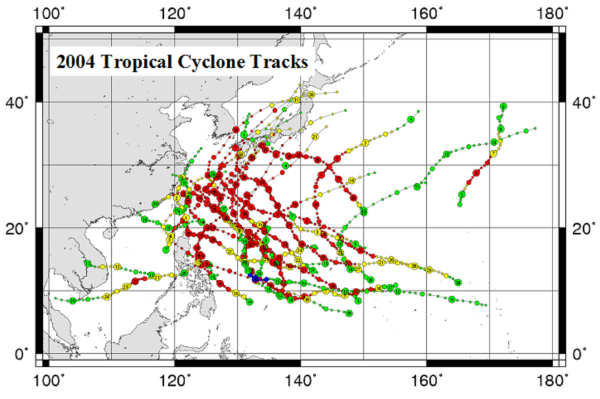

Example of typhoon tracks in the western North Pacific. A relatively active year (2004) is chosen to show

the typical development of cyclones in Micronesia, and their subsequent trajectories.

Nearly all islands of Micronesia have been hit by destructive typhoons. Guam, Yap, and the Northern Mariana Islands have the highest rates of typhoon strikes. Mile-for-mile, the frequency of named tropical cyclones passing within 70 miles of a given location is higher in parts of Micronesia than anywhere along the U.S. Gulf and eastern Seaboard. During a typical year, there are 3 tropical cyclones passing within 200 miles of Guam, and one cyclone within 60 n mi. During the year 1992, five cyclones passed within 200 miles of Guam, and three of these were direct eye passages across the island. The frequency of cyclone passages is similar for the Northern Mariana Islands, but a bit less for Yap Island and its northeastern atolls, and lesser still for Chuuk locations, Pohnpei Island, Kosrae, and the atolls of the Republic of the Marshall Islands.

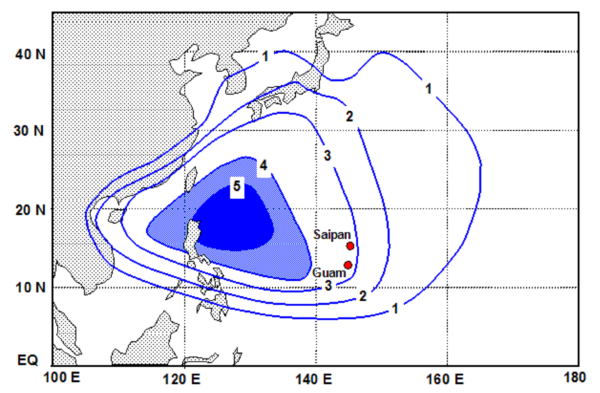

Mean annual number of tropical storms and typhoons traversing 5-degree latitude by 5-degree longitude squares.

On 02 July 2002, Tropical Storm Chata'an passed through Chuuk State delivering extreme rainfall of 15 to 20 inches in 24 hours. This heavy rain triggered many landslides, leading to 43 deaths occurring from twelve landslides on six islands. Three days later, Chata'an passed over Guam with similar extreme 24-hour rainfall, including measured one-hour rainfall totals of over 6 inches! Small slope failures throughout the so-called "badlands" of southern Guam were observed, but since this region of Guam is unpopulated, there was no loss of life there.

Typhoons and tropical storms that pass through Micronesia are also important sources of waves that impact the islands. Waves from typhoons and tropical storms can reach extreme heights (10 meters). The intensity, size and speed of motion of a tropical cyclone affects its generation of high seas, and thus higher waves may be experienced from typhoons that miss than from those that make direct hits.

ENSO causes substantial inter-annual variations in the distribution of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific basin, and within Micronesia. During El Niño, the development region for tropical cyclones shifts eastward. This substantially raises the risk of a typhoon strike on Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, and provides the islands of eastern Micronesia (e.g., Pohnpei, Kosrae, and the Marshall Islands) their almost exclusive time frame for a typhoon. During La Niña, the development region for tropical cyclones shifts to the west, and the odds of a typhoon strike are reduced at most locations in Micronesia, and nearly eliminated for locations in eastern Micronesia.

Other event types of the western North Pacific include

- Strong Trade Winds and Trade Wind Swell

- The Southwest Monsoon and Monsoon Squalls

- Other types of Thunderstorms

- Extra-tropical Storm Surf

- Extreme Tides

Other types of Thunderstorms (SW, HR, HS, Lightning)

Seasonal: Rainy Season (JASOND)

Thunderstorms are common in Micronesia, particularly during the rainy season. Because of some distinct physical processes (salt-nucleated cloud droplets) and dynamic properties (deep moisture and moist-neutral lapse rate) of the tropical marine atmosphere, lightning rates in large cumulonimbus clouds are far less over the tropical oceans than in their counterparts over continents. Nevertheless, lightning strikes have knocked out power, and caused injuries.

El Niño has a large effect on rainfall throughout Micronesia. During the winter and spring months that follow an El Niño, the rainfall is substantially reduced nearly everywhere in Micronesia. For several months, rainfall drops below values needed to sustain water resources. Following the strongest of El Niño events (e.g., 1982 and 1997) the follow-on years to these El Niño events, 1983 and 1998, were the driest in the climate records of all islands. For example, Guam's normal rainfall total during January through June is 30 inches. During January through June of 1998, only 9 inches was recorded. During this time period, over 12 percent of the island was scorched by brush fires. On Majuro, most of the municipal water is obtained from runway rain catchment. Rain water is pumped into a 33 million gallon reservoir beside the airport. One inch of rainfall provides 3 million gallons to this system. Given that the daily usage of water in Majuro is roughly 1 million gallons per day under the best of conditions, the system can quickly run low on water if rainfall does not keep up a roughly 10 inch per month pace. During El Niño related drought, rainfall can fall far short of 10 inches per month for several months, and water use must be severely curtailed.

Other event types of the western North Pacific include

- Strong Trade Winds and Trade Wind Swell

- The Southwest Monsoon and Monsoon Squalls

- Tropical Cyclones (Typhoons) , tropical storms, and tropical depressions

- Extra-tropical Storm Surf

- Extreme Tides

Extra-tropical Storm Surf (HS)

Seasonal: Winter (November-February)

Extra-tropical storms are formed at relatively high latitudes along the strongest thermal gradient between the cold polar air masses, and the warmer air masses to the south. A favored development region for intense extra-tropical storms is found south and east of Japan. Winter gales that surge southward behind the fast-moving storm systems generate large waves that then move into the lower latitudes as large swell. Normally the largest of these waves travel a great-circle route to Hawaii to become that region's famous giant surf. At times, the large swaths of cold gales pouring from Siberia out into the East Asian seas aim more southward and generate swell that travels into Micronesia. Such swell, which takes about two days to travel from its source region into Micronesia, delivers some of the highest waves annually (3 to 6+ meters in height). Only typhoons generate swell this large or larger. Characterized by moderate- to long-wave periods (10-18 seconds), North Pacific swell is most common during the winter when the strongest storms develop the mid-latitudes of the northern North Pacific. It has the greatest impact on north-facing shores.

Recent episodes of destructive inundation in the Marshall Islands and in Chuuk State were caused by large swell taking a more southerly track from its source at higher latitudes. In mid-December 2008, severe inundation and massive coastal erosion occurred throughout eastern Micronesia (Pohnpei Island, Kosrae and the Marshall Islands) and southward to the northern coastline of Papua New Guinea. During the timing of high tides, high waves washed ashore and flooded roads, homes, and crops on many islands. On Guam, there is a sea cliff on the north facing shores limiting the inundation impacts and erosion. Each year a few tourists, pole fishers, and spear fishers drown in rough sea conditions on Guam.

Blocking by Papua New Guinea and other geographical aspects keep South Pacific swell from reaching Micronesia. This swell does reach Hawaii after traveling great distances across the Pacific.

Nearly all episodes of serious coastal inundation in Micronesia are caused by high surf. Because of the bathymetry and physical properties of the reef and coastline, the islands do not experience substantial storm surge. Coastal inundation in the islands is often mistakenly referred to as storm surge. The effects of lowered atmospheric pressure during storms (inverse barometer), wind driven true storm surge, and high tides are secondary effects that can enhance the primary cause of inundation and coastal erosion, which are large waves.

Other event types of the western North Pacific include

- Strong Trade Winds and Trade Wind Swell

- The Southwest Monsoon and Monsoon Squalls

- Tropical Cyclones (Typhoons) , tropical storms, and tropical depressions

- Other types of Thunderstorms

- Extreme Tides

Extreme Tides (HS)

Seasonal: Winter Solstice (December or November-January), and La Niña

Sea level variations throughout Micronesia are modest in amplitude on most time scales owing to the generally moderate wind forcing and small tidal variation in the region. Guam and the CNMI have a mixed semidiurnal tide. Like most locations, there are two high tides and two low tides per day (semidiurnal), but they are not equal. There is an asymmetry of tidal forcing that causes one of the low tides to be substantially lower than the other low tide. This so-called Lower Low Water is the reference point (or "zero") for tide predictions in the islands. The average daily tidal range is ~0.6 m on Guam and in the Northern Mariana Islands, but is somewhat higher in eastern Micronesia (e.g., ~1.5 m at Kwajalein).

ENSO has a large influence on sea level throughout Micronesia: it is lower than normal during El Niño and higher than normal during La Niña. The range of sea level deviation caused by ENSO is on the order of 0.5 m, which is roughly the same as the range of the daily high and low tides at many islands. El Niño lowering of sea level has been associated with episodes of coral bleaching, and La Niña high stands of the sea have been associated with increased susceptibility to inundation and coastal erosion.

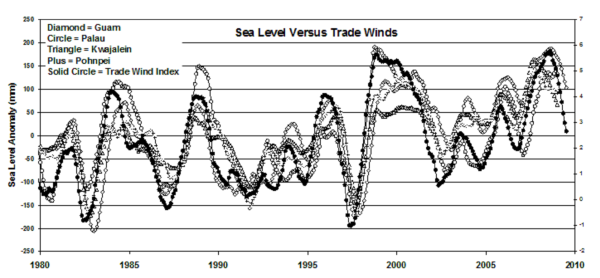

Micronesia sea level versus equatorial trade wind strength.

Plotted sea level and trade winds are 12-month moving averages. The strong correlation of the sea level

with ENSO is evident, as well as the coherent behavior of the sea level throughout Micronesia.

All islands experience spring tides twice a month. During the spring tides, the high tide is higher than at other times and the low tide is lower than at other times. The enhancement of the tidal range during spring tides may be on order of 30% of the normal tidal range, or (for Guam) nearly a 0.3 m increase in varying degrees of measure (depending on several astronomical parameters) to a higher high tide and/or to a lower low tide. Some of the astronomical parameters that govern the tides (e.g., the phase of the moon, the timing of the moon's crossing of the equator, the declination of the sun, the timing of the moon's closest and farthest point of approach to earth, etc.) result in long term cycles of differential tidal influence. Two such cycles, the perigean tides and the Saros Cycle yield periods of extreme tidal forcing that recur at intervals of 411.78 days and 18.03 years, respectively. Enhancement of tidal forcing, per se, does not normally cause dangerous inundation, but amplifies wave set-up and wave run-up of any high surf that might occur. The tidal range throughout Micronesia reaches its annual peak at the winter and summer solstices, in June and December, when the sun is at its maximum declination relative to the equator. On Guam, the lower low tide is most extreme (falling to datum-referenced values as low as -0.25 m) in December and June, with the timing of the reef-exposing lower low tide in the morning hours during December and in the afternoon hours during June.

Tidal and other fluctuations in water level are superimposed on a long-term upward trend which has increased mean sea level by approximately 15 cm over the past century. This rising background level contributes to a growing concern for an increased susceptibility to inundation events and persistent and increasing rates of coastal erosion.

Hazardous 4-5 meter surf crashes along the reef face at Pago Bay, Guam, and wave set-up and wave run-up inundate the shoreline.

This surf was caused by a typhoon passing to the south of the island.

Other event types of the western North Pacific include